Everything you need to know about Japanese rice wine

By Linda Burum for epicurious.com

Rich and mellow, crisp and dry, or as floral as a perfume—the wide-ranging flavors of sake, Japan’s traditional rice-based alcoholic beverage, often surprises those who’ve experienced only futsu-shu—mass-produced sake served heated in ceramic flasks. Premium sakes, frequently consumed slightly chilled in stemware to reveal their subtle nature, are known as jizake, which translates roughly as “country style.” But for Japanese connoisseurs, the term implies much more.

Jizake makers employ time-consuming, detail-oriented procedures eschewed by futsu-shu producers. In some cases regional rice varieties, local water, and specific yeasts may contribute to a sake’s individuality and distinctive flavor. Of the nearly 1,500 sake makers—known as kuras—scattered across all but one of Japan’s provinces, most have been family-run for many generations. Now their sakes are finding a sophisticated international audience of devotees who are discovering their tantalizing nuances and low acidity, and how sake can equal wine in the way it enhances many foods.

An Elegant Evolution

For centuries sake (pronounced sah-KEH rather than sah-Kee) has been as central to Japanese life as the rice from which it is made. Bottles are placed on home altars for the delectation of the gods in the hopes that they will bestow good luck on the family. At traditional celebrations, a rite known as kagami-biraki, the bashing open of a sake keg with a wooden mallet, commemorates everything from weddings and housewarmings to company mergers.

Sakes vary in their level of sweetness, acidity, and price

Every Japanese schoolchild knows that the first sake was concocted by the god Susanoonomikoto, who used it to inebriate a fierce dragon before slaying him with his magic sword. The story may be apocryphal (although several present-day kura produce a “Dragon Slayer”–brand sake), but we do know, from transcriptions of oral histories, that Japanese villagers in ancient times figured out how to make a primitive form of sake. When wild airborne yeasts found their way into moldy rice and began to ferment, an alcoholic brew, closer to a milky white porridge than to the clear liquid we know today, became the drink of choice for festivities. The ancients soon concluded that the rice mold could be propagated and used to make subsequent sake batches. They thought the mold was a gift from the gods.

The brew’s virtues weren’t lost on the aristocracy, either. Just about the time wet rice cultivation caught on in the third century, it was noted in the Kojiki, one of Japan’s oldest historical chronicles, that the Japanese imperial court commissioned a foreign brewmaster from China, where rice liquors were already enjoyed. Later the Engi-shiki, a written code on court behavior, informed of sake refinements in the 9th and 10th century. Although the stuff was still milky or yellow-colored, producers were beginning to strain the sediment. Sake was reserved for nobles and priests, but by the 13th-century, descendants of the court’s sake makers had set up independent kura. At the time, 342 of them were open for business in Kyoto alone, and aficionados were already discriminating between the sakes of different makers.

It wasn’t until the 16th century, with increasing technical advances, that sakes similar to those we have today began to evolve. Rice polishing, facilitated by the water wheel, resulted in a clearer, purer brew. Sake’s stability improved vastly by heating it to 149 degrees Fahrenheit—a pasteurization process, the Japanese love to point out—in use 300 years before Pasteur made his famed discovery.

WWII changed modern sake considerably, but unfortunately not for the best. Rice shortages forced brewers to stretch their pure rice sakes by adding a good amount of brewer’s alcohol and glucose. The practice denigrated sake but nevertheless, futsu-shus were widely consumed.

From Rice Grain to Sake

Sake, often called rice wine, is showing up in all types of restaurants—not just Japanese ones. But because it’s fermented from a grain rather than fruit juice, sake isn’t technically a wine. As with grain-based beer, the process of sake making involves converting grain starch to simple sugars before fermenting them into alcohol. In sake brewing, a particular mold, koji-kin (Aspergillus oryzae), performs the conversion by releasing enzymes into cooked rice grains. This saccharification and then fermentation are sequential in beer brewing; in sake making, they occur simultaneously.

But the foundation for sake’s fermentation is the critical interim step of making a starter mash (or pulp) known colloquially as the moto. The mash, made up of koji-infused rice, yeast, water, and usually lactic acid, ferments in a small tank for about 15 days. Alive with hungry yeast, the moto mash is transferred to large fermentation tanks along with plain cooked rice and water. Working in tandem, the koji breaks down the new rice starch while the yeast transforms the resulting sugar into alcohol. This method, termed multiple parallel fermentation, may be tricky to say after a few sakes, but the process magically yields a 20-percent mash alcohol content, the highest in any nondistilled beverage.

When fermentation is complete, brewer’s alcohol may or may not be added to the mash. Next the sake is strained of its rice lees, filtered for clarity, blended with a bit of water to balance its flavor, and then pasteurized and bottled.

Aided by computer technology and machines, these procedures may be fully automated. Premium sake (jizakes), however, require many more intricate and time-consuming steps than this oversimplified explanation reveals. There may be delicate specialty rice that needs to be washed by hand, or slower, longer fermentation periods.

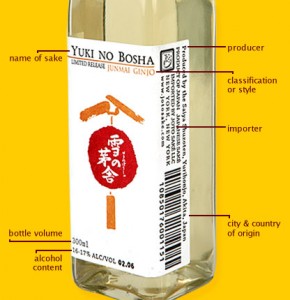

Labeling Premium Sake

Labels offer clues to how sakes will taste. Fortunately, an increasing number of them are being translated into English. But even on untranslated labels, the numbers indicating sweetness, acidity, and other attributes, such as the polish rate, can help inform a purchase. Although the designations are usually in Japanese, some imports are sold to non-Japanese wine shops using Roman numerals.

Sakes are categorized according to how much the rice has been polished. As a general rule, the more highly polished the rice, the more delicate and aromatic the resulting sake will be; fats and amino acids in the grain’s outer layer contribute heavier, funkier flavors, while the heart of the grain, nearly pure starch, converts to beautifully fermentable sugar.

The classification of junmai ginjo indicates this is a premium sake that has no added alcohol. Some bottles will also display levels of sweetness and acidity.

Labels indicate the polish rate or percentage of rice removed during polishing with the term semaibuai, which is actually the amount of rice remaining after the polish. A semaibuai of 50 percent indicates a daiginjo, the most aromatic and delicate sake category. A semaibuai of 60 percent designates a ginjo—slightly less delicate and aromatic—while sakes having a 70 percent semaibuai are the more robust and traditional junmais and their smoother more sophisticated cousins, honjozos.

Although the names ginjo and daiginjo mean premium and superpremium in Japanese, most sake devotees agree that these classifications are not strict quality rankings. Rather, they indicate a sake’s flavor and body. Honjozo is a relatively modern premium sake in which a small amount of brewer’s alcohol added during the final fermenting stages unleashes and heightens fukumi-ka, the secondary fragrances and flavors. Strict Sake Brewer’s Association guidelines dictate that honjozos, unlike garden-variety sakes, must contain less than 10 percent added alcohol.

But to make matters more confusing, even when alcohol has been added to a ginjo or daiginjo, these will not be designated honjozo. You can tell when a premium sake has been made without any added alcohol because it bears the prefix junmai (pure rice). Thus junmai daiginjo and junmai ginjo have no added alcohol, while ginjo and daiginjo may have added alcohol. A sake termed honjozo will have a lower (70 percent) polish rate) than the former two, but higher than a common futsushu.

Tokubetsu junmai, meaning “special” junmai, indicates the use of exceptional handling techniques, unique rice strains, or rice more highly polished than the minimum requirements.

Additional sake styles include: Genshus: Unlike most sakes, which are diluted slightly to balance their flavor and achieve a 16- to 17-percent alcohol level, genshus are full-strength sakes that hold up beautifully on the rocks.

Namazakes: These sakes are left unpasteurized. They must be stored refrigerated, and even then they change fairly quickly as their fermentation continues. Some aficionados prefer the light sweetness of a just-brewed namazake; others enjoy the more mature tart version. These days some namazakes are being packed in cans to extend their keeping time.

Nigoris: Cloudy with rice particles, these sakes have a rich, sweet taste—and this sweetness comes from lees left in the brew or added back after filtration. Nigoris are popular at weddings and will complement highly spicy or rich fried foods. A subset of nigoris, sparkling sakes, fairly new to the international sake market, are fun to drink. Although many are soda pop–like futsu-shus, one can easily find junmai ginjo and even daiginjo sparklers.

Sweetness, Dryness, and Acidity

The sake meter values (SMV), also called Nihonshu-do, indicate residual sugars. On average, the SMV scale runs between +7 to -4. Some bottles show this information, the sweetness or dryness of a sake, on the back of the label. But not all. Numbers higher than four indicate varying degrees of dryness. Zero is theoretically neutral, while minus numbers tend toward sweet. Is sweet sake considered tacky or just another option? Château D’yquem or Manischewitz? That’s a difficult question. As with wine, there are highly regarded sweet sakes (ginkobai, a junmai infused with plums, and also kijoshu, which is almost like port or Sauternes and made by substituting sake for half the water in the fermenting mash). And there are lower-grade, glucose-added sakes. As with the D’yquems, high-quality sweet sakes are often “dessert” sakes. Less treacly but gently sweet sakes are recommended as an aperitif. High acidity modifies the perception of sweetness. Although labels provide the following indications of acidity—the mildest at .08 to the most tart at 2.0—numbers aren’t the whole story, as other factors intervene. But they’re a start.

Matching Sake with Food

Daiginjos: Generally delicate, nuanced, aromatic, and tasting of ripe fruit, daiginjos do best as an aperitif or a match for mild fish or subtly seasoned appetizers.

Ginjos: Slightly more fruity and assertive than daiginjos, these light, smooth sakes match well with sushi, seafood, and light pastas.

Junmais: Often rustic, with a woody nose, junmais are bolder and more assertive still. They can be paired with bigger flavors—grilled chicken, pork, or tempura.

Tokubetsu Junmais: With their special designation, these sakes give brewers leeway to create distinctive flavors. Most are bold and meaty and will stand up to steaks, oilier foods, and rich sauces.

Honjozos: These are often excellent with a wide range of flavors due to a cleaner, drier taste, moderate acidity, and crisp finish.

Most sakes are best consumed when young—under a year old. A caveat: The shipping dates on some bottles follow what is known as the Emperor’s Calendar. Unless you’re Japanese, they likely won’t make sense. It’s best to find a trustworthy retailer and inquire about the bottle’s age.

Although small ceramic cups and cedar boxes called masu have long been traditional drinking vessels, nowadays most sake sommeliers serve premium sake in wine glasses so the aromas can be better appreciated. But the traditional salutation when drinking sake remains “Kampai” (“Empty cup”)!

Sharaku Artisan Sake (junmai daiginjo)

Price: $32 for 720ml Sweetness & Acidity Level: SMV +3 acidity 1.1

Region: Miyaizumi Meijo kura, from the region of Fukushima.

Sharaku embodies the classic daiginjo style with its nectarlike aromas of ripe plum, Asian pear, and hints of sweet rice. A light acidity hidden among its sweet notes and ample body creates impeccable balance in this mellow brew. Pairings: sashimi, grilled white fish, fresh stir-fried vegetables.

Sato no Homare Junmai Ginjo (Pride of the Village)

Price: $43 for 750ml Sweetness & Acidity Level: SMV +3 acidity 1.3

Region: Sudo Honkekura, from the region of Ibaraki

From the oldest working kura in Japan, this refined light brew has herbs and berry fruit in the nose and hints of tropical fruit flavor, yet it drinks slightly dry and exhibits a whistle-clean finish. Pairings: scallops, sashimi, light appetizers.

Otokoyama Kimoto Junmai

Price: $45 for 1.8 liter bottle Sweetness & Acidity Level: SMV +4 acidity 1.8 Region: Otokoyama kura, from the region of Hokkaido

An old-fashioned moto preparation method contributes a rich complexity and multiple flavor layerings that combine hints of dry fruit and a deep nuttiness in this powerful, full-bodied dry sake. Pairings: sushi, grilled foods.

Michinoku Onikoroshi Honjozo

Price: $24 for 750 ml Sweetness & Acidity Level: SMV +10 acidity 1.5 Region: Miyagi Shurui kura, from the region of Miyagi

The name “Demon Slayer” might suggest a harsh forceful brew. Not so with this ultradry sake that still manages to display the detectable fruity notes of green apple, strawberry jam, and traces of cinnamon. Pairings: grilled meats and a wide variety of well-seasoned foods.

Rihaku (Dreamy Clouds) Tokubetsu Junmai Nigori

Price: $43 for 750ml Sweetness & Acidity Level: SMV +3 acidity 1.6 Region: Rihaku Shuzo kura, from the region of Shimane

Although filled with tropical fruit flavors that layer in sweetness, a delicate texture and dry finish contribute to an all-around balance and this sake’s potential to complement a wide variety of dishes. Pairings: yakitori, halibut, smoked fish.